Lessons of the Barbary Plague

Way back in 2006, I reviewed a book for The Tyee that clarified for me the role that racism plays in spreading diseases:

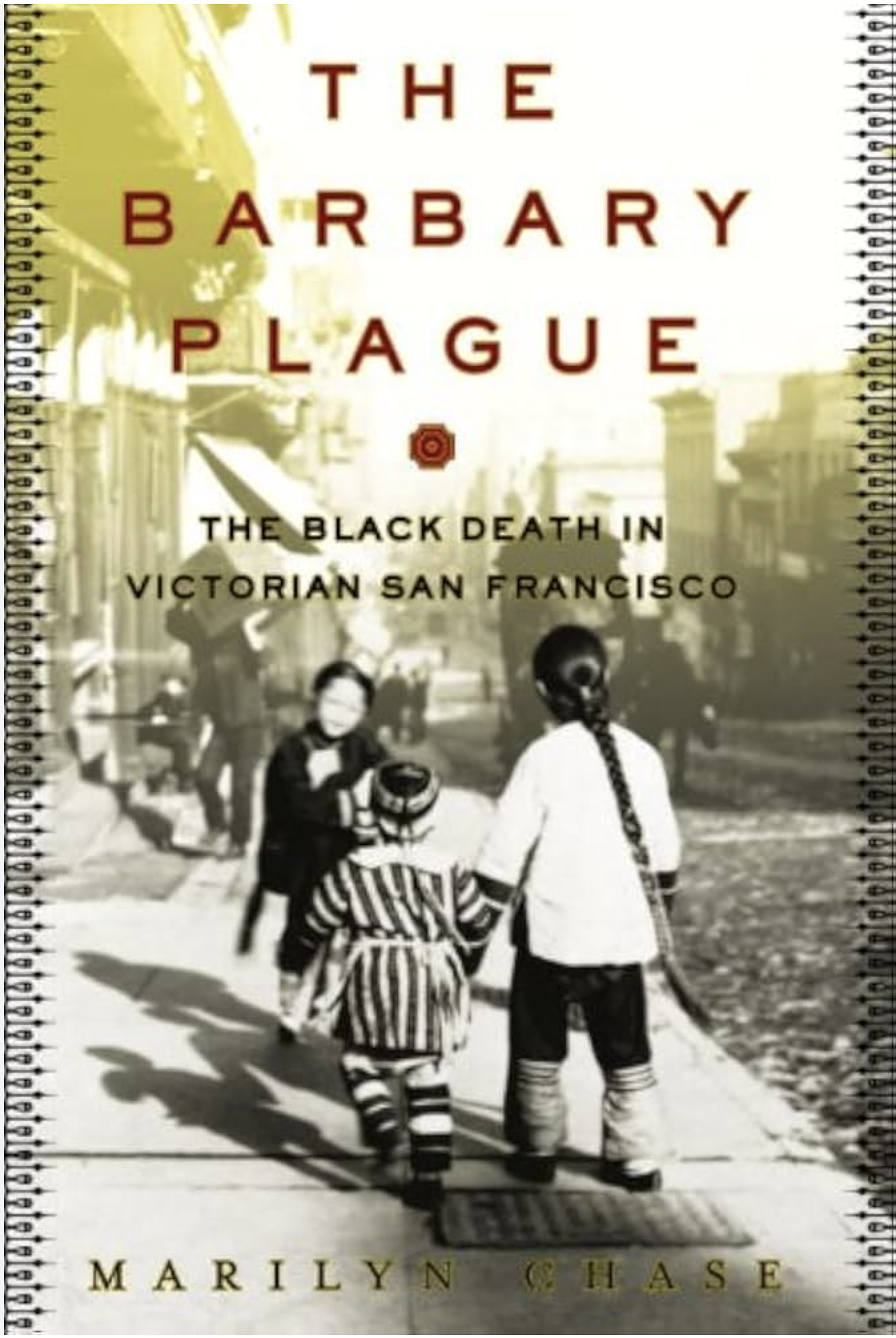

In 2003, when avian flu was just emerging in a couple of Korean poultry farms, American writer Marilyn Chase published The Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco. Reading it recently, I thought it pointed to the same factors that are at work in the impending H5N1 pandemic.

The first of these factors is old-fashioned medical ignorance. When the first cases of plague broke out in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1900, most doctors didn’t even know the vector: rat fleas.

The plague bacillus had been isolated and identified in Hong Kong only six years earlier. Alexandre Yersin used advanced techniques to identify what became known as Yersinia pestis. Most California physicians considered bacteriology a lot of high-tech mumbo jumbo. They also ignored the recent Australian finding of plague bacilli in the stomachs of rats.

Doctors knew that rats could carry plague, but not that they could transmit it via fleas to humans—even though dead rats had been a signature of bubonic plague since the Black Death of the 14th century.

Today, our ignorance is more sophisticated: we can read the genes of the influenza virus, we can even revive the H1N1 virus that caused the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-19, but we can’t predict the time or manner of H5N1′s mutation into a truly deadly disease.

Racism redux?

The second factor is racism. Race relations in San Francisco a century ago were (by our standards) appalling. Whites considered the Chinese not only innately filthy and degraded, but far more vulnerable to plague than whites. In a state where politicians got elected on a White California platform, it was hard to muster the will to confront a disease afflicting only Chinese.

For their part, the Chinese were terrified of the white majority, and especially of white doctors. They regarded routine autopsies of plague victims as a horrible desecration, and soon began smuggling sick persons (and corpses) out of the city. As a result, medical authorities never knew just how many Chinese died of the plague (or recovered from it).

Not until a new public-health boss, Rupert Blue, took over the plague campaign, did the Chinese begin to cooperate. He got results by respectful treatment of patients and the whole community, and by astute use of a good translator.

Today’s racism is also more sophisticated. But we still tend to equate Asian diseases with diseased Asians. In 2003, white Canadians were even avoiding Chinese restaurants for fear of catching SARS. Jean Chretien and much of his cabinet had to chow down in public on mushu pork and egg fuyung, just to revive the industry.